When I first started building brackets and structural frames, figuring out how to calculate fillet weld strength felt like some kind of engineering puzzle. I could lay a clean bead with MIG or flux core, but knowing whether that weld was actually strong enough for the load? That part wasn’t so obvious.

It turns out weld strength depends on more than just a nice-looking bead — you’ve got to consider fillet size, leg length, throat thickness, metal thickness, and even how well your joint prep was done.

Misjudging it can mean anything from wasted filler metal to a weld that fails under stress, and nobody wants that. Once I learned the simple formulas and real-world tricks for estimating weld capacity, my projects got safer, stronger, and a lot more professional. Stick around — I’ll walk you through how to calculate fillet weld strength the practical way, without overthinking it.

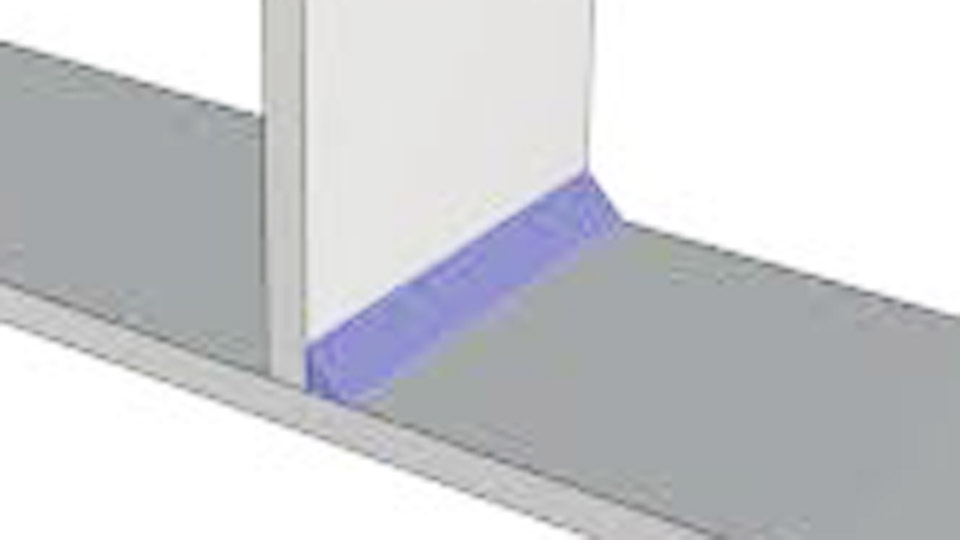

Image by structuralbasics

What Exactly Is Fillet Weld Strength and Why Should You Care

A fillet weld is that triangular bead you run in the corner of a T-joint, lap joint, or inside corner. Its strength comes from throat thickness — the shortest distance from the root to the face of the weld — not leg size (even though we always call out leg size on drawings).

Get the throat wrong and you can have a beautiful-looking 3/8-inch leg that’s actually weaker than an ugly 3/16-inch fillet laid by the new guy on his third day. I see this all the time on trailers and equipment racks: guys oversize the weld because “bigger is better,” burn through thin material, warp everything, and still end up under strength because the throat never developed.

Real-world stakes? I once watched a 5-ton scissor lift platform drop six inches because four 5/16 fillets on the pivot arms were calculated for static load only — nobody accounted for the dynamic shock when the operator bounced it off a curb. The math would have told us to go up one leg size or switch to 80 ksi wire. Instead we spent three days on our backs in a parking lot at 2 a.m. fixing it.

The Magic Formula Every Fabricator Actually Uses

Here’s the formula I’ve had taped inside my welding hood for fifteen years (AWS D1.1, Clause 2.4.2.9 if you ever want to look it up, but you don’t need the book on the floor):

Allowable load (lbs per linear inch) = 0.6 × F_u × t_e × L

Or, the one I actually use 90% of the time because it’s simpler and conservative:

Strength per inch = 0.707 × leg size × 0.6 × electrode tensile strength

No, that’s not exactly how the code phrases it, but that’s how it shakes out for 70 ksi filler metal like ER70S-6 or E7018.

Let me break it down English-style:

- Take your leg size (say 1/4 inch = 0.25)

- Multiply by 0.707 (that’s 1/√2 — turns leg into effective throat for a perfect 45° fillet)

- Multiply by allowable stress — usually 0.3 × ultimate tensile of the filler for static loads in older codes, or 0.6 × tensile of the electrode for shear in D1.1

- That gives you pounds per inch of weld length

For a 1/4-inch fillet with E70 wire on A36 steel:

0.25 × 0.707 × 0.6 × 70,000 ÷ 1000 = about 7,400 lbs per linear inch

That single number has saved my butt more times than I can count.

Matching Base Metal, Filler Metal, and Process — Because I’ve Seen the Disasters

I run into shops that just grab whatever stick or wire is open and wonder why the weld cracks two weeks later. Strength calculations are worthless if the filler doesn’t match.

Quick cheat sheet I keep on my phone:

- A36 or A572 base → E7018 sticks or ER70S-6 wire (70 ksi minimum)

- A500 tubing → same deal, but preheat 150° if it’s thick and cold outside

- 4130 or T1 plate → E80 or ER80S-D2, match the strength or you’re asking for trouble

- Aluminum 6061 → 5356 or 4043, calculate throat the same way but use 0.6 × 33 ksi allowable instead of 70

I learned the hard way on a 4130 roll cage: used 70 ksi wire because “it’s what we had.” First autocross event, the cage folded like a lawn chair right at the fillet. Lesson cost me a weekend and a very embarrassed customer.

Step-by-Step: Calculating a Real T-Joint Like We Do on Truck Frames

Let’s say you’re building a receiver hitch for a 1-ton truck. Drawing calls for 1/4-inch fillets on 3×3×1/4 angle to 1/4 plate, 8 inches long each side, four welds total.

- Figure applied load — worst case, tongue weight 1,500 lbs plus dynamic factor of 3 (bouncing down a washboard road) = 4,500 lbs total downward.

- That load is carried by four welds in shear, but really it’s two T-joints, each with two fillets.

- Shear on each fillet ≈ 2,250 lbs over 8 inches = 281 lbs/inch required.

- Using the formula: 0.25 leg × 0.707 × 0.6 × 70 = 7,418 lbs/inch capacity.

- 7,418 ÷ 281 = factor of safety about 26. That’s ridiculous — we can drop to 3/16 leg and still be at FS 17.

I actually built that exact hitch with 3/16 fillets, saved 40 minutes of welding time, no burn-through, and it’s been dragging trailers for five years now.

When Fillet Size Isn’t Enough — Partial Penetration vs Complete, Convex vs Concave

Here’s something they don’t teach in vo-tech: a concave fillet has a smaller throat than the leg size would suggest. A super convex “stack of dimes” can have a bigger throat. I always aim slightly convex on structural stuff — gives me 10–15% more strength without increasing leg size.

Also, if your fit-up has a gap bigger than 1/16, you just lost throat. I carry 1/16 and 3/32 shim stock in my box to check root opening before I strike an arc on anything that carries load.

Machine Settings That Actually Get You Full Strength

MIG guys: if you’re spraying 0.035 ER70S-6 at 17 volts and 180 ipm because “it looks pretty,” you’re probably cold. I want 350–400 ipm wire speed and 24–26 volts on 1/4 material for a true 1/4 leg. Heat is your friend for penetration and throat development.

Stick welders: E7018 loves 1/8 rod at 125–140 amps for 1/4 fillets. Drag it slow, pause in the corners, keep that keyhole open. I’ve pulled apart plenty of “strong-looking” welds that were just tacked together with cold lap.

Common Mistakes I Still See After 20 Years (and How to Fix Them)

- Measuring leg size instead of throat — carry a fillet gauge and actually check throat on test plates.

- Forgetting direction of loading — fillet welds are strongest at 45° to load. If load is parallel to the weld, derate 30–50%.

- Using prequalified joint details as gospel without checking actual thickness — the AWS tables assume perfect 45° and no gap.

- Calculating for static only — anything that moves needs a 2–4× dynamic factor depending on how abusive the operator is.

Quick Reference Table I Keep on the Wall

| Leg Size (in) | Effective Throat (in) | Strength per Inch (kip) E70 filler | Strength per Inch (kip) E100 filler |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1/8 | 0.088 | 3.7 | 5.3 |

| 3/16 | 0.133 | 5.6 | 8.0 |

| 1/4 | 0.177 | 7.4 | 10.6 |

| 5/16 | 0.221 | 9.3 | 13.3 |

| 3/8 | 0.265 | 11.1 | 15.9 |

Print it, laminate it, stick it next to the grinder. You’ll look like a wizard when you tell the boss we can drop two weld sizes and still sleep at night.

Dynamic Loading and Fatigue — The Silent Killer Most Shops Ignore

Trailer hitches, crane booms, anything that sees repeated loading — static calculation is only step one. AWS has fatigue curves, but here’s the rule I live by: if it shakes, rattles, or gets hit with impacts, double the calculated size or use a better process (like moving from fillet to PJP groove).

I rebuilt a log splitter frame last year that kept cracking 5/16 fillets every season. Switched to 3/8 fillets laid with 100 ksi wire and added gussets — problem gone for three years and counting.

Aluminum Fillets — Same Math, Different Numbers

People freak out when they switch to aluminum, but it’s honestly easier. 5356 wire, 0.6 × 33 ksi allowable shear:

1/4-inch leg = 0.25 × 0.707 × 19,800 ≈ 3,500 lbs/inch

That’s why aluminum boat hulls have huge fillets — the base metal is only 30–40 ksi to begin with. I always push boat guys toward 5356 over 4043 for structural because it’s stronger and less crack-sensitive.

Putting It All Together on the Shop Floor

Here’s my exact checklist when someone hands me a new fabrication print:

- What’s the load and direction?

- Base metal grade and thickness?

- Filler I have on hand that matches?

- Run the numbers for required throat.

- Add my safety factor (2.5 minimum, 4+ if it moves).

- Pick the smallest leg size that works — saves rod, time, heat input, distortion.

- Set the machine hot enough to guarantee penetration.

- Weld slightly convex, check throat with gauge on scrap first.

Do that every time and you’ll never get the 3 a.m. phone call that something broke.

Conclusion

After you finish reading this, you’re not just another guy who can lay a pretty bead — you can look at any T-joint or lap and know, within a couple hundred pounds, exactly what it’s going to carry before you ever strike an arc. That’s real power in a fabrication shop.

After that the engineer oversizes everything “to be safe,” you can hand him the calculation showing 3/16 does the job of his 3/8 and save the company real money.

Next time the boss asks if that repair on the loader arm is good enough, you can say yes with confidence instead of hope.

Always weld a quick test coupon the same thickness and position, break it in the vice with a hammer, and look at the throat. If it’s shiny and full thickness, your settings are golden. If it’s porous or half-developed, turn the heat up before you touch the real part.

FAQ

What’s the difference between leg size and throat size in a fillet weld?

Leg size is how far the weld metal spreads up each plate — what you measure with a fillet gauge. Throat is the shortest distance through the weld from root to face — that’s what actually carries load. For a perfect 45° fillet, throat = leg × 0.707.

Can I use the same fillet size calculation for stainless steel?

Yes, but match the filler — 70 ksi for 308/309, 80 ksi for 316L stuff. The 0.6 multiplier still applies. Just watch heat input or you’ll sugar the weld pool.

How much stronger is a convex fillet than a concave one?

Roughly 15–25% in throat thickness if you stack it proud. I always aim slightly convex on anything structural — free strength.

Do I need to derate fillet welds loaded parallel to their length?

Absolutely — shear strength drops to about 60–70% of transverse. Put the load across the weld whenever possible, or oversize heavily.

Is there a simple phone app for fillet weld calculations?

Yeah, I use “WeldCalc” and “Fillet Weld Strength” — both free, both accurate enough for shop use. Punch in leg size, filler, and steel grade, and they spit out capacity instantly.